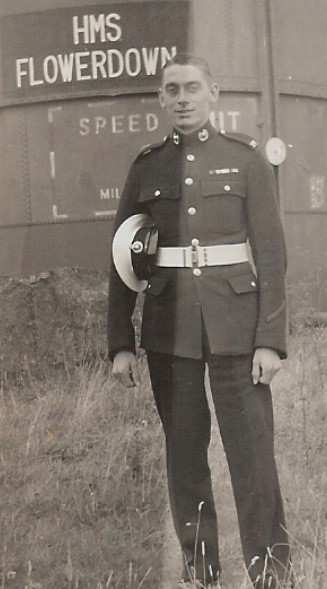

The Royal Marines Association were lucky enough to secure a visit with former Royal Marine James (Jim) Wren, 100 years old, and his wife Margaret at their family home to hear him recount his amazing story first-hand.

He is truly an inspirational former Marine and Jim and Margaret are the true epitome of the Corps Family. It was an honour and a privilege to meet with them and talk about his experiences as a Japanese Prisoner of war during the 1940s.

Royal Marine Jim Wren was aboard HMS Repulse when it was sunk by Japanese bombers in 1941. Hundreds of people died, and Jim was lucky enough to count himself of one of the few survivors. He aligned himself with an Army unit who were defending the British fortress of Singapore.

Although valiant efforts were made to save the lives of hundreds of civilian men, women and children, the Japanese had taken control of the routes, blocking their escape. Jim, along with others on board, were taken prisoner.

The conditions in Japanese Prisoner of War Camps were atrocious, and many did not survive, Jim was a prisoner for three and a half years, and he was still a prisoner when he found out that the war was over.

Jim was only 19 when he tried to ‘join up’ in the war effort, he had been turned away from the RAF and the Army, when he was recruited by his uncle.

“One day, my uncle who was a retired Royal Marine said he had been recalled on reserve. He came home one weekend and said, ‘Join us, we’re taking recruits,’ and that’s how I came to be in the Royal Marines.”

After completing the 8-month training course at Stonehouse he was posted to join the Battlecruiser HMS Repulse in the Autumn of 1940. They spent months as part of the Arctic and Atlantic Convoys, delivering weapons to Allied troops. This was a dangerous job, and they were a target for German attack.

“It was gruelling, especially up in the Arctic. The small ships we were with had a particularly tough time of it. But it was all part of the job.

“HMS Repulse was a very well-organised ship. We had a great captain, and everything ran quite smoothly. The camaraderie was marvellous. I met some really super men in those days. I can never forget those men.”

HMS Repulse and HMS Prince of Wales were re-tasked with deterring Japanese aggression and arrived in Singapore on 2nd December 1941. Within 5 days Japan had declared war on the British Empire and had begun to pre-emptively attack Allied Forces. Jim was shocked at how ‘prepared’ the Japanese were and recalls thinking that they had been ‘underestimated.’

At 11:13 on the 10th of December the Japanese air force attacked, two bombs missed but the third struck.

“It all happened so quickly, we were on our usual mid-morning break, all on the mess deck having a cup of tea, and the alarm was sounded. I dropped my tea and headed to my action station.

“There was such a confusion going on. The noise was terrific, it was one big noisy battle. Gun crews of all descriptions involved. There was no panic though, we’d been through the routines so regularly that we just got on it. Everyone knew their role and we had such a good crew. We all had faith in each other.

“The first bomb that hit dropped right behind me. Fortunately, it went down 2 or 3 decks before it exploded. I didn’t have time to think about it at that point.”

HMS Repulse sank at 12:33 10th December.

Jim said that he “didn’t even hear the actual call for abandon ship” but it was only when he had left that he could see the devastation that had been caused. The sea was slick black from tar and oil, and it was every man for himself. Jim managed to find debris to stay afloat and was later dragged onto a Carley float. He was sick from the amount of oil he had swallowed.

“I lost many good friends. I can still see images of them today in the mess deck. I was with them every day. I can still see their faces and remember them.”

He was rescued by HMS Electra, and they were taken back to Singapore, where they were welcomed with a tot of rum. As the Royal Marines were one of the very few units that were trained for jungle warfare, they were sent to protect the retreating Army and suffered huge losses.

The Japanese began to get a foothold in Singapore and Jim and the other Royal Marines began to evacuate the area, loading men women and children into boats, most of which were sadly sunk or captured at sea. Jim left Singapore under the cover of darkness, facing Japanese resistance almost immediately.

On the 15th of February their boat was illuminated by the searchlight of a Japanese destroyer, they had been captured.

“I won’t ever forget seeing them. Nobody could speak Japanese, and the Japanese sailors came onboard, tearing around the ship, shouting, and hitting and striking people, and the children were absolutely frightened to death. I can see the fear on their faces even today.

The Japanese separated the military personnel from the civilians, Jim was held in an abandoned building without water or sanitation. Jim described the treatment at that point as ‘abominable,’ they were stripped of every valuable thing they had, left only with a small amount of clothing.

Prisoners continued to arrive to the warehouse they were kept in, they slept on concrete floors and were given little to eat. Jim and the other POWs were then taken to a disused school in Palembang, Sumatra.

“Again, we were sleeping on a brick floor with no bedding, sanitation or water. Oil drums were used as toilets which had to be taken away and emptied daily. The water which was brought in was unsuitable for drinking unless boiled.

They were stripped of any basic human rights, and this was before the ‘working parties’ had begun. The men were told to sign papers saying they would not try to escape, scared of more men facing punishment and death and even further deterioration in conditions, they decided to sign. Although they had started receiving food and water again, they were being forced to work. Jim described the experience as being “slavery of the first order”.

“When the Japanese captured us, I had been sleeping on the upper deck and I took my boots off. In the confusion someone took one of my boots instead of their own, so I was left with two boots of different sizes. I could not manage with the smaller shoe, so I cut the heel off.”

For three and a half years Jim was kept as a Prisoner of War enduring barbaric conditions and suffered brutality daily. Jim witnessed horrific atrocities that he still finds difficult to talk bout years later. He recalls that a prisoner who had struck a guard, after he returned to work injured to earn food rations, was taken away and never seen again.

Despite the atrocious conditions, Jim says the bond between the prisoners was strong. Jim, and a group of around 30 Royal Marines supported each other and looked out for one another. They did their best to protect each other from being beaten if they were struggling with the work.

Prisoners of War had no contact with the outside world, they were fed information with regards to the war but had no way of knowing if what they were being told was true. This made it very difficult for the men, not knowing if or when they would be set free.

In August of 1945 working parties were stopped, that indicated to the Prisoners that help was getting closer. A few days after being stood down the men were called out to roll call, a Japanese Commander came out and said “the war is over” then fled. Jim said “You can just imagine. Some chaps just stood there, dumbfounded. Others hugged their chum, next to him, others just went to the ground and shed a few tears. I shed a few tears; I can tell you.

“It was an emotional reaction through my whole body. At that stage, we had almost got to a point of no return.”

The Allied forces came to the aid of the prisoners, and they were flown to Singapore by the Australian Air Force flew them to Singapore.

Jim was given clothing and equipment and was put on troopship HMS Antenor to return home. The journey took six weeks, and they stopped once at a port in the Suez Canal to get kitted up with winter clothing.

He arrived in Liverpool on 27th October 1945.

When Jim was posted in Scotland in 1940, he had met his future wife, Margaret, he was utterly shocked that she stood waiting for him alongside his mother and father when he arrived in Sussex.

They had not communicated for all those years, and although Margaret had set letters, they were returned to her marked ‘unknown’. Margaret had been working on munitions throughout the war, but when she received the news that Jim was coming home, she moved to Sussex so she could be there for his return.

“Fortunately, all the family (except one brother in the Army who was heading to Singapore at the same time I was leaving it) managed to get home that night and we had a whole family gathering. There were some tears that day too.”

Jim and Margaret were married the following year.

Jim served on HMS Vanguard for the remaining 6 years of his service, although his health was not what it should have been he wanted to stick it out until retirement. After 12 years in the service, Jim worked with the Parks Department in Salisbury, and then as a groundsman and gardener for a local school until he retired. He is a member of COFEPOW – The Children (& Families) of the Far East Prisoners of War organisation and wants people to remember what happened in the Far East during the war, as he continues to feel the mental scars today.

“It’s had an effect on me mentally over the years. I find it rather difficult to communicate, or converse with people. That whole experience is in the back of my mind all the time, because some things never go away.

“I’m glad the war ended, but it’s important to remember the world has changed too. The Japanese today are different people to the way they were then. And what happened at the end of war shouldn’t be forgotten either. The atom bomb saved my life, and the lives of thousands of men, but it took lives as well. It’s a thing I never want to see again. Never.”

Prince Charles has now commissioned a portrait of Jim, to be hung in Buckingham Palace. Painted by artist Eileen Hogan from the Royal School of Drawing.